The Professor and the Siren, an Exploration

Unusual memories and the primordial root of nobility

She spoke and thus was I overwhelmed, after her smile and smell, by the third and greatest of her charms: her voice. It was a bit guttural, husky, resounding with countless harmonics; behind the words could be discerned the sluggish undertow of summer seas, the whisper of receding beach foam, the wind passing over lunar tides. The song of the Sirens, Corbera, does not exist; the music that cannot be escaped is their voice alone.

I want to call attention to a curious short story written by Giuseppe di Lampedusa which has to do with the relationship between a professor and a siren, a literal mermaid. If you know Lampedusa you are probably familiar with his singular and acclaimed novel, The Leopard, an introspective and melancholic exploration of the decline of a great Sicilian family and the eclipse of their exquisite tradition-bound world by the forces of progress. The novel is a massively eminent and haunting read, the culmination of a lifetime of literary immersion (Lampedusa spent his life reading but did not begin to write until just a few years before his death), and if you have not read it or watched the 1963 film adaption you really must, but today I want to explore his only other complete and much-lesser known work: “The Professor and the Siren,” which, despite numbering only a scant few dozen pages, in many ways is even more ambitious than his novel and emerges freshly relevant to the currents of online culture. “La Sirena,” as it was published in Italian, offers a story that plumbs the depths of Sicily’s lost pagan past to offer the promise of total, beautiful, and terrible transformation.

It’s also a summer story, replete with romance and longing and the sea. It has to do with impossible love, and men and the nature of women; it’s ideal for reading aloud to a lover in the post-coital languors of the early evening. If only for this reason alone you should read it, but of course there is much more to its lovely depths. Be warned, from here forward you can expect spoilers. Men, be further advised: once you read this story you might find yourself irrevocably mermaid-pilled, forever unsatisfied with earthly relations and possessed with a longing which only the sea can answer. Thus cautioned, we proceed.

Lampedusa was a prince. Born in 1896 as the heir to the Duke of Palma, he grew up in a world of palaces, with sprawling gardens, servants, visits from traveling nobles who anchored their yachts in the bay before Palermo in their tours about the Mediterranean, and most of all, literature, for Lampedusa was an only child. After the sad death of his sister he was raised entirely in the company of adults and spent long hours immersed in reading, a habit that came to define his life, first as a pastime, and then as the decline of his family became evident in his adulthood, as a passion and retreat from the diminishment they suffered as their holdings were broken up and their influence obsolesced over the course of decades. For this reason it is impossible to separate Lampedusa from his work; his great novel is an attempt to capture the fullness of the old traditions and the great characters of his fading aristocratic world and preserve them in literary form against the corrosive forces of modernity. The novel is unbearably beautiful but also melancholic: many contemporary critics, while recognizing its merits, accused it of hopelessness, of painting a beautiful picture of dignity amidst decline with no redeeming mechanism for redemption. In this, both the critics and Lampedusa can be forgiven: how would it be possible to conceive of the continuation of the old Sicilian aristocracy against the titanic forces of liberalism which swept the globe, and even bombed his childhood home? There’s just no possible way to imagine it, so Lampedusa paints the image of a proud noble, last of his line, who like Spengler’s soldier at Pompeii, ‘bravely follows his path to the destined end’ and so achieves the epitome of that old ideal of the Roman nobility: a good death, which is won not only for his character Don Fabrizio, but for Lampedusa himself in the act of making this final account of his life and class.

But while The Leopard is massive, fatalistic and final, The Siren is the little codicil that casts the prior testament in different light entirely, the quicksilver door that offers the possibility of escape. For if the Leopard is an attempt to reconcile the decline of the Christian aristocracy to modernity, The Siren encloses even this history by reaching directly to an even remoter pagan past which offers the hope of renewal.

For Lampedusa’s Siren is not a monster, she is a lover. She is half god and half beast, with nothing human about her, but explicitly carnal. She reveals to the young Professor not only in her words, but in her body, a knowledge of nature and the ancients which can only come through complete immersion and boundless, bottomless love, love to the point of death. She swims, she eats live fish only, she makes love and speaks in Attic poetry:

“Not only did she display in the carnal act a cheerfulness and delicacy altogether contrary to wretched and animal lust, but her speech was of a powerful immediacy, the likes of which I have only ever found in a few great poets. Not for nothing was she the daughter of Calliope: Oblivious to all cultures, ignorant of all wisdom, disdainful of any moral constraint whatsoever, she was nevertheless part of the source of all culture, of all knowledge, of all ethics, and she knew how to express this primitive superiority of hers in terms of rugged beauty. ‘I am everything because I am only the stream of life, free of accident. I am immortal because all deaths converge in me, from that of the hake just now that of Zeus; gathered in me they once again become life, not individual and particular but belonging to nature and thus free.’”

Lampedusa’s Siren is a marvelous character, a vortex of mythic vitality, union of high and low, of tidal feminine attractive force. Not for nothing did Lampedusa’s Professor swear off mortal women after his encounter with her. Lighea (for that is the Siren’s name) contains something of the promise that all women offer; an avenue to eternity, but distilled with ecstatic re-encounter with the spirit of the ancients and the swelling, romantic, insatiable wanderlust which manifests as love for the physical personification of the sea. Like the Ovidian gods, she is a conduit to metamorphosis. “What potions have I drunk of Siren tears?” asks Lampedusa’s Professor. In his encounter with her he undergoes a “sea-change / into something rich and strange.” To love her is to love life never-ending at the root of all things, to love adventure which is life’s expansion, to love love itself. In reading, you too might fall in love with her and become mermaid-pilled, and that is precisely Lampedusa’s design.

Like his novel The Leopard, which was rejected by publishers several times, even weeks before Lampedusa’s death, the success of his Siren story depends even more self-consciously on a final act of transmission. “Corbera,” says the elderly professor in the scene just before he tells his tale, “I need you.” Exactly like Lampedusa himself, the senatorial professor carries an old kind of knowledge, “a vital, almost carnal sense of classical antiquity” of which he must unburden himself before he can finally merge with his beloved classical world in a final act of extinguishment and transformation. The double recounting, first by the weary professor to his pupil Corbera, then by Corbera to we, the readers, accomplishes this transmission by presenting the Siren and all her enchantments to the world, opening the possibility that a new generation might fall in love with her and the world she represents; a lost portal re-opened through which the spirit of the ancient world can once again pour into the world.

Does all this seem familiar? Does it remind you of BAP? In reading the story, with its Professor, a towering eminence in the classics, do you imagine meeting BAP in some dingy bar while he leans forward and very seriously says “I mus tell you story of how I once had encounter (sexual) with a mermaid?” Would you laugh (and break the spell) or, like Corbera, would you believe?

For indeed, today we see in online spaces a Cambrian explosion of beings, a door to the ancient world opened by BAP but which now expands with tumultuous ferment in myriad expressions: history buffs, longing aesthetic posters, art girls, legions of statue pfps, poets, philosophers, futurist sculptors, solar bodybuilders, holy surfers.

This cavalcade surges through a new conceptual terrain on the open sweep of the internet. Our desires for exploration, for richness, for strangeness and ludicrous excesses are refracted through signifiers marking the entry into a younger more immediate existence. We sense that just out of reach, below the surface, another world awaits, and know that possibly if we allow ourselves to be carried along these channels of aesthetic and turbulent desire that maybe, in the strange heart of it all we might encounter something, some secret, that washes the old mundane tints out of our hearts and leaves us transformed.

What would Lampedusa say to all of this? Would he be gratified to see the words of his Don Fabrizio echoed through the timeline? “I must live a certain way.” I believe that, not without an expression of cynical bemusement, he would be delighted. His wish to live according to his traditions, his aesthetic sense, to remain true to his essential being in defiance of the world; this is our wish now. He shares our skepticism with all newly puffed up authorities: “Nothing has been revealed to them” he spits of contemporary classicists. Moreover, like the Professor needs Corbera to hear his story, the success of Lampedusa’s attempt depends on us to receive it. Therefore his final triumph is marked by our successful reception, not only in the sense of simply reading, but through our internalization and re-expression of his literature.

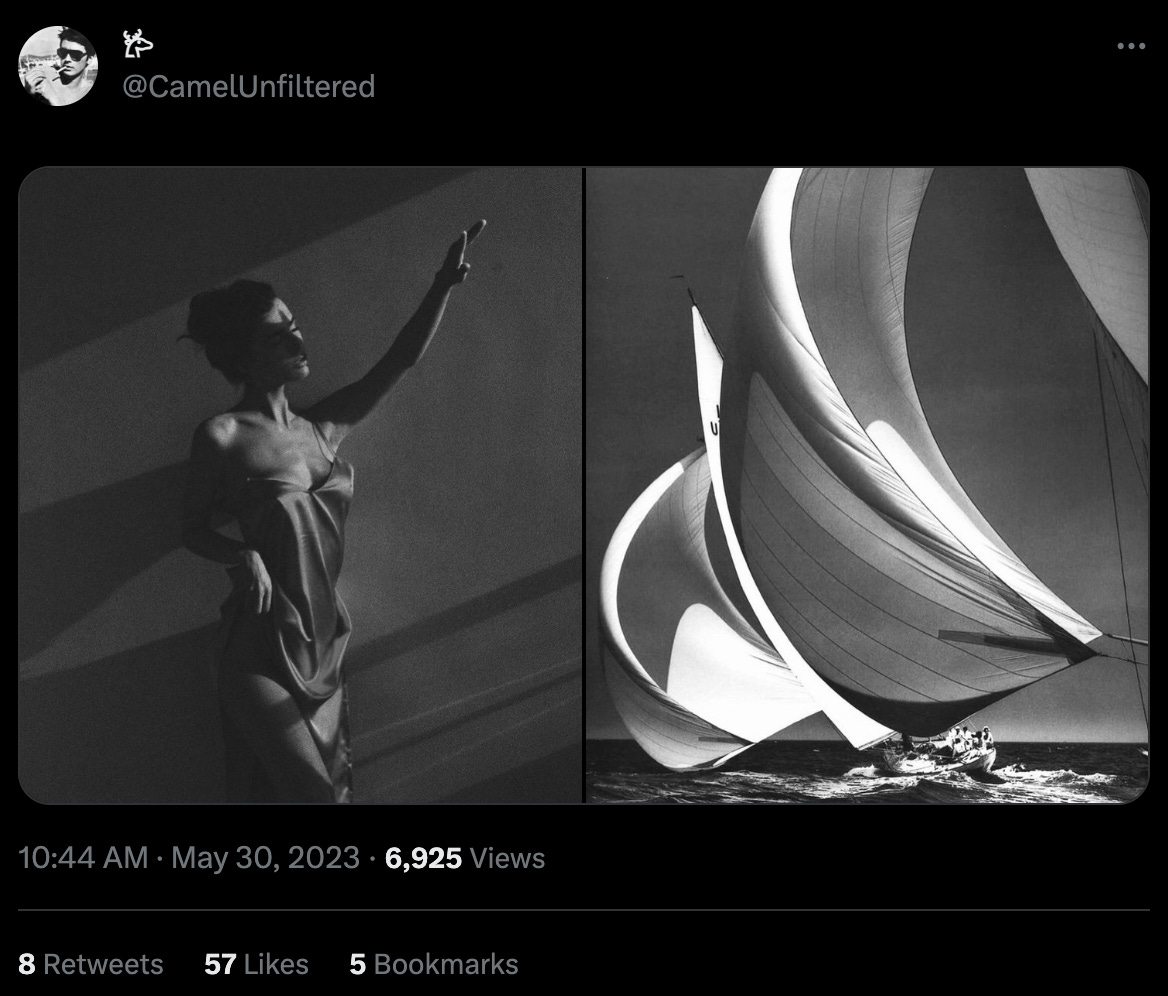

Then there is the call of the sea. There are certain accounts that dedicate themselves to a particularly sirenic aesthetic. Their posts are images of the ocean; waves and blowing foam, billowing sails, gauzy mists, disturbed waters, sprays, and luminous atmospheres charged with erotic potential. The women (and sometimes men) who people these images are wet, unencumbered, completely free and libidinous. They emerge directly from the water. What are they doing there? Merely swimming? How did they get there? Do they live on the boat? What do they eat? It doesn’t matter; they are elemental manifestations, their purpose is to entice but moreso to personify and signify the ocean itself and the romance of departure and journey. Like the Siren they present a template for a distinct kind of life in which the heavy, terrestrial associations of rootedness and fixity of form are cast away. They are the magnetic symbol that hovers on the horizon. On the open sea you can do anything you want, be anyone you want, go anywhere you want. The ocean is a place of change and motive forces, and through immersion in its imagery these aesthetic seekers invoke its transformative powers as well as open psychic distance from context-laden mundanity and scolding mandarinate influences.

BAP speak of this. In his article published in MANS WORLD magazine, “The Open Steppe of the Sea,” he makes the link between the open sea, which for the ancient Greeks was a sphere of exploration, conquest, and ultimate freedom, and the effect produced in the mentality and conceptual world of all descendant Western peoples. One does not simply push out into the infinity of the abyss and emerge unchanged. That sense of vastness, of willingness to contend with the infinite stamps the seafarer irrevocably, he will forever be unsatisfied with mere littoral waters just as the Professor was left bereft for most of his life, having already been made a citizen of a different world by Lighea’s kiss. Even further, the ocean, with unbound disposition, is constant variation; wind and tide and weather, the diversity of lands and peoples encountered along foreign shores, the currents that sometimes carry ships along or jumble them together: familiarity with all of these makes a mental character adept at flexibility and easy recombination of forms. The creativity of the West may well have been born at sea. Not for nothing was Odysseus, most cunning of the Greeks, a seafarer first and foremost.

Submersions

But we must go deeper.

What was Lampedusa seeking in the creation of his siren? It was the primordial root of all nobility: the undivided existence brimming with life, the spirit which is not just tenuously associated with the gods through custom or morality, but is actually a full and living expression of their existence, where the esthlos (the excellent, powerful, and good) vibrate at the power and immediacy of it.

This is how the early ancients experienced the world. In the Illiad, which is the fount of Western culture, we see men completely unhindered by self-doubt, undivided personalities who act with great impression on the world around them. They converse freely with the gods, and this gives their actions and emotions the vehemence of force.

As Julian Jaynes, the rebel investigator of early consciousness writes: “The characters of the Iliad do not sit down and think out what to do. They have no conscious minds such as we say we have, and certainly no introspections. It is impossible for us with our subjectivity to appreciate what it was like. When Agammemnon, king of men, robs Achilles of his mistress, it is a god that grasps Achilles by his yellow hair and warns him not to strike Agamemnon. It is a god who then rises out of the gray sea and consoles him in his tears of wrath on the beach by his black ships, a god who whispers low to Helen to sweep her heart with homesick longing, a god who hides Paris in a mist in front of the attacking Menelaus, a god who tells Glaucus to take bronze for gold, a god who leads the armies into battle, who speaks to each soldier at the turning points, who debates and teaches Hector what he must do, who urges the soldiers on or defeats them by casting them in spells or drawing mists over their visual fields.”

The theory that Jaynes puts forward is expansive and would constitute a sweeping re-understanding of human nature if it were widely accepted, but in essence he argues that consciousness as we moderns understand it, in which the individual is a mental world unto himself, with subjectivity, self-observation, and conscious manipulation of mental word-forms, is something that only arises after the development of language, and even then only after a long delay.

“How is this possible?” you might ask. “Isn’t consciousness necessary for intelligence?” Not so, Jaynes argues. He severs the act of judgement from consciousness through a series of thought experiments. Have you ever known exactly what to say, without knowing how you knew? Are you not more fluent when a few drinks have relieved your tongue from the observation of your conscious mind? In the midst of playing sports, wouldn’t you perhaps stumble if you let yourself think about what you were doing in the middle of your ecstatic drive to the goal?

Jaynes presents an existence, during the intervening period between the rise of human language and the laboriously-erected structures of reason, where the individual experienced suggestions and motive forces in the form of literal voices, interpreted as deities, in the way a schizophrenic might today. The normal experience of the individual was therefore pure immediacy and uninterrupted continuity, an eternal existence in the present without self-consciousness, while during times of stress or indecision the irresistible voices of motivation or insight would manifest. For those closest to the gods, then, the inner voice is pure inspiration, while for subordinates, their voice is merely a derivative of the great chieftains.

How would it be like to experience such a person? He would speak with decision and immediacy. He would not lie. His voice would carry the weight of authority and radiate divine integrity. Imagine some situation (which has happened constantly through history) in which a young military commander, in order to rally the troops, delivers a concise plan and then steps forward to expose himself to danger, contemptuous at even the most furious efforts of the enemy. Do you see how your mind is filled with his words of urging, how he grows in stature before your eyes? Do you see how the objections of recalcitrant elements melt away like sodden tissue, even in their own minds? Now his speech and affect inspire you, and hearts beating as one, you and your troop are stirred to action. You have internalized his words, assimilated them into your own consciousness, and are now “animated” by them.

Something of this experience conveys only an iota of the power and weight that words, and the mental apparition of words, could impress at the dawn of experience when they still had their newness.

[Achilles] is faster, sharper, bigger, brighter and more important than other men. He is more beautiful. He rides on deeper emotional currents … He is semi-divine and wholly precious. Other men cannot even aspire to be like him. At his most resplendent, men cannot even bear to look at him. He is just above and beyond.

This immediacy in the sense of physical presence of the forceful encounter between persons, physical and verbal expressions of divine truth, and depth of personality is what characterized the ancient nobility at the dawn of it all. Their lack of self consciousness was not a flaw, but the connector to the great continuity of existence. “Indeed the Greeks saw time & history …. as a densely woven fabric of genealogies unfolding through spacetime, brilliantly exalted here and there by the favor of a god …” (CWU, twitter). While the individual had existence, he didn’t experience himself as such; he was conceptualized as a manifestation of a larger whole. Not even his desires and decisions were his own, these he always attributed to his gods.

We should therefore understand Lampedusa’s novel and his later siren story as constituting a first attempt, and then a second more urgent attempt, to convey the fullness of his aristocratic world-view, an apologia for the distinct cosmic vision that animates his dying class. In this light, we see how The Leopard is predicated on tradition as the differentiator and mechanism of access to historical continuity which is the mark of nobility: “the significance of a noble family lies entirely in its traditions, that is in its vital memories; and he was last to have any unusual memories,” he says of Fabrizio on his deathbed. Meanwhile, in The Professor and the Siren, Lampedusa, after his failures to publish his novel, reaches for stronger stuff. He gives us a direct revelation of divinity and the experience of it, in the sense of a theophany, when a god sheds his disguise and reveals to a mortal his true form, a dazzling display that always connotated serious consequences for the mortals who observed it.

With these things in mind we revisit Lighea. Her voice “overwhelms,” it possesses a “powerful immediacy.” She is “oblivious to wisdom” and, “any moral constraint whatsoever.” Nevertheless she is the “source of all culture, of all knowledge, of all ethics” and these things are expressed in her physicality and in her speech. When she justifies herself she says “I am everything because I am only the stream of life, free of accident. I am immortal because all deaths converge in me, … gathered in me they once again become life, not individual and particular but belonging to nature and thus free.” Now do you see what this means?

How opposed then, is Freud’s ego, the rational “executive” of the personality, to this mode of life? The consciousness, with its airy fantasies, self-justifications, and pretensions, its anxious modes of rumination and plodding analytic methodology, is the undisputed ruler of the modern personality. We are rational beings you see. We make decisions with spreadsheets.

But how we long to shake this consciousness off! We drink to stupefaction. We watch films to “carry us away” and suspend its action. We hope that its self-recriminations can stop for a moment so we can speak in public or approach a woman. We meditate to empty it. We take up exercises to “clear our heads” and perhaps outrun it. Sometimes we outright drug it into submission. At night we long to sleep, and extinguish it altogether.

In the realm of deliberation, there is no measure too extreme to relieve us of “conscious thinking.” To sit down and actively think about something is the hardest and most hateful task in the world; we outsource our thinking to machines, rubrics, checklists, doctors, experts, the media, the legislature. It often seems that we can only be happy when we can cease to think!

Then there is sex, which aside from victory in sports or combat, is the most immediate experience of all with its inescapable physicality; perhaps it is the last means, in a world where religious experience has been diminished, where the ego can be actually dissolved for the span of a few breathless moments. Not for nothing are Lampedusa’s Lighea as well as the sirens of the online aesthetic seekers charged with libidinal energy, for through these encounters can be glimpsed a portal back to the ecstatic unconscious world. The body, and specifically the beautiful body is therefore the entry point into this zone of transformation, as well as its fullest expression.

The story ends when Lampedusa’s professor finally throws himself into the sea to re-unite with his beloved Lighea and redeem her promise: “You are young and handsome. You should follow me into the sea now and escape sorrows and old age,” She says. “You would come to my home beneath enormous mountains of motionless dark water, where all is silent calm so innate that those possess it no longer even perceive it.” According to the psychological constructions that we have explored here, we can plainly see that the ego has extinguished itself, and so the Professor, shed of all his heady connotations, achieves final union with the inexhaustible primordial continuity represented by his lover.

In the story this metamorphosis is rendered ambiguously. The shockingly cynical coda, with its perfunctory and ugly description of the destruction of the last artifacts left by the Professor by Allied forces in WWII, does not suggest a successful transition. However, we the readers know that Corbera is not left with only a shard of pottery (which Lampedusa paints, winkingly, with the image of Odysseus’ feet tied to the mast), he is also the bearer of the Professor’s extraordinary tale, carrying with it the pregnant implications of transformation with regards to future readers. If we recall the scene earlier in the story when the Professor sneers at Odysseus’ attempts at preservation against the Siren’s charms, we know that “no one escapes.” Lampedusa, in leaving this little piece of pottery engraved with depiction of futile defense, is telling us he knows, with full aristocratic self-confidence, that we the readers, having heard the voice of the Siren, will likewise never escape, but be indelibly altered.

Such a wonderful piece Palous, thank you so much for developing it and sharing it. Truly fed.

You somehow manage to be devastatingly funny without breaking the flow of the poetic.

This must be where Patrick Rothfus found inspiration for his character of Felurian, if not, then the egregos of it can be found there too.

I read the Leopard at one of the lowest points in my life and I must say, it only encouraged me in my attempt to kms, I was filled with a furious disgust and dejected hopelessness. I had forgotten the title and have been wondering which book it was for years, happy to have found it, so I can read it again, thank you for that, and for a brilliantly written piece!