Total Nuclear Death

A warning

I’ve recently been playing around with Nuclear War Simulator which is exactly like it sounds: less a game and more a tool. Originally used by researchers at Princeton and the Pentagon, it’s now available on Steam. Here there are no points to win, only scenarios to run: each one terrifying in both scale and particulars. Did you know that today’s ICBMs carry up to ten warheads each? Each warhead, typically 30 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, can be independently targeted to strike a different city, or the same city if you really want to be sure the job is done. Russia has an arsenal of at least 400 such missiles in addition to nuclear weapons carried on bombers or submarines, for an estimated total of 5,977 warheads as of 2022. The United States has 5,428. All of these are available to you in Nuclear War Simulator, where you can push a button to launch them in great curving arcs over the Arctic Circle to rain down nuclear fire from the stratosphere on Russian and American cities below.

Once the bombs have dropped, you can run casualty simulations to see the death totals in fine-grained detail. There are myriad ways to die when getting nuked: instant radiation burns, crushed in falling buildings, burned in the good old-fashioned type of fires which would rage through the wreckage after being ignited by the heat of the blast, or death from radiation poisoning from lingering fallout carried on the wind. To make things terrifyingly personal, you can even place icons on the map representing friends and family and watch how they’d fare if positioned in a car, in a basement under a concrete building, or ominously “in the open.”

“I began (like many of us) to wonder in my idle moments whether my house was within the blast radius of a Russian bomb.”

So obviously, in this day of heightened tension with Russia, when we learn through a zoomer whistleblower that US forces are significantly more engaged with fighting Russia in Ukraine than the public, and maybe even Congress, had been led to believe, I began (like many of us) to wonder in my idle moments whether my house was within the blast radius of a Russian bomb. There are various kinds of hypothetical scenarios involving the use of nuclear weapons, including those in which the nations involved decide to target the enemy’s population centers instead of merely just their military forces. To get a sense of the greatest possible destruction, this MAX DEATH scenario was the one I chose to run. Results discussed below:

Summary:

Plan: OPEN RISOP Countervalue + Counterforce 2021.06.01

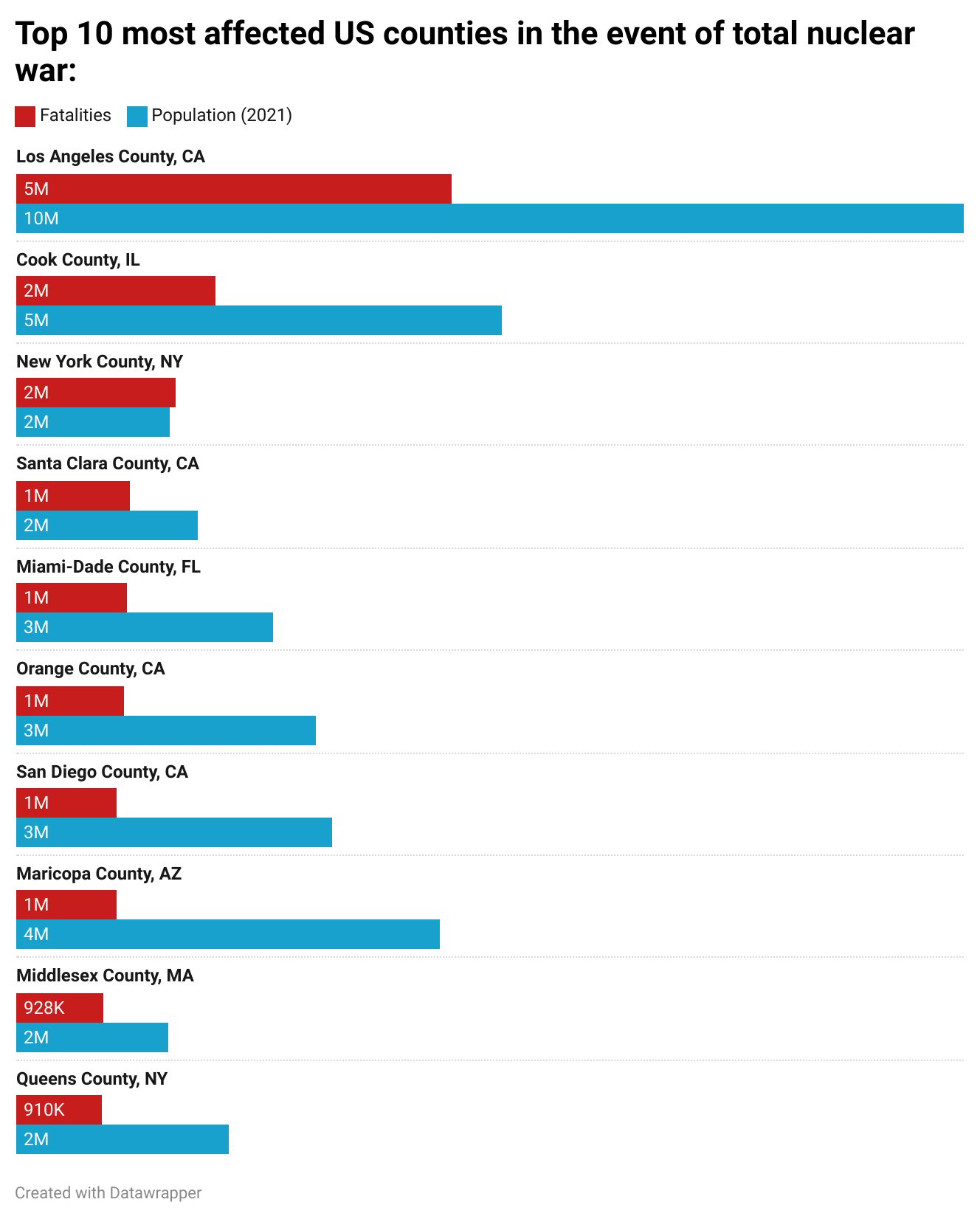

US fatalities: 71 Million

82% of US petroleum refining capability destroyed (3.2 million barrels / day remaining)

18% of electric power plant capacity destroyed (926,000 megawatt remaining)

Top 50 seaports destroyed: 99% of US shipping capacity by tons destroyed

All Class B (major commercial) airports destroyed

Vast swathes of prime US farmland irradiated

Soot in the stratosphere: 19 Tg (from US alone)

A war of this kind would instantly plunge the United States and Russia (and any other nations dragged into the conflict) into a world lit only by fire. Those left alive nearest any blasts could expect very little assistance: FEMA guidance calls for response teams to stay out of Dangerous Radiation Zones and leave survivors to shelter and evacuate as best they can under their own efforts. In addition to radiation, response teams could expect to contend with damaged infrastructure, roadways choked with disabled vehicles, knocked out power, and enormous fires as structures and fuel lines ignited. Most immediate efforts would therefore be limited to firefighting on the perimeter and camps to treat any survivors who managed to self-evacuate. The attack would last several hours or days, involving multiple rounds of exchange as the US and Russia exhausted missiles, then submarine-launched weapons, then finally cruise-type weapons launched from bombers as cleanup. By the end of it most cities would be left in smoking ruins and the US population would be reduced by 20%.

“At that moment, our aircraft emerged from between two cloud layers and down below in the gap a huge bright orange ball was emerging. The ball was powerful and arrogant like Jupiter. Slowly and silently it crept upwards ... Having broken through the thick layer of clouds it kept growing. It seemed to suck the whole Earth into it. The spectacle was fantastic, unreal, supernatural.” (Soviet cameraman, eyewitness to Tsar Bomba detonation)

One of the only ways to get a sense of what it would actually be like to experience something like this is to read the landmark piece written by John Hersey in The New Yorker in 1946. This article, which tells the story of Hiroshima bomb survivors in their own words, caused a sensation among the American public when it was first published by revealing for the first time the destructive power of the atom bomb.

Here’s a list of things that would be instantly wiped out or irreparably irradiated: museums full of art, famous buildings, historical artifacts, churches, communications hubs, bridges, roads, airports, rail infrastructure, data centers, water reservoirs, schools and universities, libraries, record archives, major news media offices, tens of millions of units of housing, running water, and the internet.

Survivors of WW2 describe how even if they managed to return home, the war displaced them twice: because their original towns were destroyed and rebuilt in unfamiliar configurations, the places where they’d made their lives had disappeared. Even if you managed to survive America would never be the same place again: the places you associate with America would literally be gone.

The Difficulties

After surviving the initial bombardment the real difficulties would set in. Currently in North America we use 10 calories of fossil fuel energy to produce one calorie of food energy. With 80% of refinery capacity knocked out, the surviving government would face the difficult decision of how to allocate fuel. The needs would be pressing: power generation, response efforts, re-building critical infrastructure, and defense would all need be balanced against food production. In 1979 the US Senate commissioned a fascinating study involving a fictional scenario in which one US city survived and became a regional hub for refugees and reconstruction efforts. Somewhat optimistically they concluded that starvation could be held at bay temporarily, but hoarding and food conflicts would abound. Unscathed areas would be flooded with refugees and State governments, concerned primarily with the business of surviving, would be little capable of cooperation anywhere beyond their own borders. The challenges involved in organizing a largely displaced population without any use of organizing systems such as we have come to rely on like digital records, electronic payment systems, supply chain and delivery systems, or even the internet, would be enormous.

The economy would of course implode. The dollar would collapse in value. Most companies would be destroyed; even if not directly implicated the subsequent collapse in demand for goods and services of all kinds would render them irrelevant. The wholesale destruction of assets would cause a chain of defaults that would reverberate around the globe. Markets would be thrown into turmoil and prices of basic necessities like oil, repair parts, and foodstuffs would be basically unobtainable at any price, creating immediate incentives for conflict even in areas not directly affected.

Then there are darker predictions. “Nuclear famine” is the idea that fine soot propelled into the atmosphere in a large-scale nuclear conflict would obscure the sun for a number of years, causing plunging global temperatures and interfering with crop growth. Dismissed as alarmist fantasies during the Cold War, the subject of nuclear winter is now being examined by a new generation of researchers equipped with better data and computer models. A 2022 study published in Nature found that even 5 Tg of soot from burning cities, fuel stores, and forest fires would be enough to cause global famine. With so many nations dependent on food imports, even a modest disruption of crop production and shipping capability would have large effects. More extreme scenarios with more soot predict up to 5 billion lives lost from starvation. In the simulation I ran, which accounted for only destruction in the United States, soot totals were calculated to be at 20 Tg. With Russia included, soot totals could easily be at least double.

Aftermath

And I beheld when he had opened the sixth seal, and, lo, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood. And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind. And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together; and every mountain and island were moved out of their places. And the kings of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains, and the mighty men, and every bondman, and every free man, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains. And said to the mountains and rocks, Fall on us, and hide us from the face of him that sitteth on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb. For the great day of his wrath is come; and who shall be able to stand?

A war of this kind would bookend history, the most significant event since the birth of Christ. Certainly the only possible comparisons would be the inundation myths from pre-history, or apocalyptic scripture, putting it firmly on the plane of cosmic significance for all humanity. Every other calamity, including both World Wars, would be a mere footnote in comparison. How would our descendants understand this event? Would they see it as an accident? A chastisement? Who would they blame? What would the sense of dislocation be to experience apocalypse and still survive? What new myths would they make?

For while it is certain that one kind of world would pass away, humanity as a whole would live on. There are enough nations on earth that would survive relatively unscathed that rebuilding would be accomplished eventually. The world that emerged following such an event would be significantly humbled, but also hardened for having survived, and they would look forward with a new sense of resilience and readiness to face the challenges of rebuilding. A century after the dust settled, the pall of tragedy would begin to fade.

So in trying to understand what a post-war world would be like, I resolved to to not see it as an end, but as a beginning.

Brave New World

To understand what a post-nuclear world would look like, it’s helpful to understand who would be left out of the exchange. In the scenario of a war between the US and Russia, non-membership in NATO or lack of US alliance, as well as distance from Russia’s borders are factors likely to aid survival. Countries that don’t possess nukes are less likely to be targeted or drawn into regional exchanges: there is always the possibility that once the bombs started flying regional powers would use the war as an opportunity to attack each other. The new world leaders would therefore be those with intact industrial capacity and access to oil who managed to avoid an attack.

China, Japan, and India

If China, Japan, and India managed to avoid being involved in the war, they would emerge as the new world powers, marking the beginning of an Asian century. Likewise for Canada, if it survived, though I believe it likely that in a MAD scenario it would be targeted simply to hinder American reconstruction.

Besides these, the countries that would fare the best would be those with a large industrial base and population, internal oil reserves, high education, and high stability. Leading players would also be free from hostile neighbors who might take advantage of the chaos to launch an attack of their own, or who would fight with them for resources in the years following the war.

All surviving countries would have to contend with the collapse of the world economic system and the slowdown or halt of international trade. As long as there were ships, ports, and oil, trade could still theoretically occur but would probably be possible only on an ad-hoc emergency basis. Our current world shipping networks are designed to sustain certain levels of volume. After a war they would simply be unprofitable to operate, and without the U.S. Navy, would be subject to piracy. It would be possible to organize national convoys if agreements could be secured with other nations, but the reality is that trade would become infrequent, risky, and expensive. Even without a nuclear winter, the most food-dependent nations would likely face mass starvations.

In this world, one clear winner would be Australia. Its defensible island position, access to natural resources, and educated population would give it natural advantages in a post-war world. Indonesia would be a regional leader as well.

In the western hemisphere, Brazil would enjoy a new status as the largest, most industrialized nation. Mexico would come in close second, but would have the disadvantage of potentially being overrun with American refugees or otherwise drawn into reconstruction efforts on unfavorable terms.

Middle eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, or UAE have the benefit of oil reserves but would probably not be able to avoid being drawn into conflicts that would compromise their ability to participate in world events.

Of the European countries, Spain would fare the best. It’s situated furthest from Russia’s borders and does not host American nuclear weapons (that we know of). With the exception of the U.S. naval base at Rota, it is unlikely to be targeted.

Beyond direct impacts, surviving nations would have to navigate a world completely unmoored from the organizing assumptions of the last several decades. Gone would be American military power and economic projection, which support today’s integrated global order. Concerns about markets, or climate change, or gender equality, or urbanization would become irrelevant compared to concerns for survival. An atmosphere of fear and uncertainty would dominate until some kind of peace was re-established. The specter of submarines still cruising beneath the waves, still at the command of zombie nations, would surely haunt every country on earth.

Fundamental Transformations

How would we understand the sudden void of the United States? It would be like kicking out the pillars of the earth. Inside the corpse of the fallen titan, new ways of life would be made.

On the level of demographics, the U.S. would be a different nation. With 71 million fatalities, most of them from urban areas, the power of cities would be shattered, maybe forever. The national balance of power would instantly shift to rural areas. Simply as a thought exercise, because in the event of a war elections would of course be suspended, perhaps indefinitely, consider that if you re-ran the 2020 election with the loss of the most populous cities Trump would have won with 56%. With this in mind, there is no one on earth who should be working harder to prevent a nuclear war than Democratic Party politicians:

Urbanity itself as a concept would be in doubt. Leaving aside the sudden destruction of the cities, all of society would prioritize dispersion over density in the interest of defense. Concentrations of people and embodied wealth would be seen as foolish, an invitation to attack, and a prospect to be greatly feared. Vulnerable coastal locations would likely be abandoned with exception of necessary port districts. Geographic capitals would be situated in the interior of the country, both for better proximity to new dispersed formations of small towns, and for better defense in depth from missile weapons.

National post-war priorities would have a profound effect on the beliefs of the people. The enormous and immediate needs for reconstruction, re-population, basic sustenance, and the restoration of order would set all other projects aside for decades. Those communities that survived would necessarily have adopted mindsets of toughness, resourcefulness, fecundity, and optimism for the future in the face of unimaginable difficulties. The people who survived the bombs a century after the destruction would be a profoundly different people than the ones who went in.

Then there is the form of government to consider. The United States government has a series of war plans called “Continuity of Government” that outline how the Federal government would ensure its survival in the event of a nuclear war. First architected in the 60’s, these plans called for a network of hardened sites where government officials would take shelter in the event of catastrophe. The principal locations are by now public knowledge, like Raven Rock in Pennsylvania, which is essentially a hollow mountain where DOD would take shelter, and Mt. Weather in Virginia, for the executive branch.

Many of these plans are still classified, but in essence the US governing apparatus would emerge from these shelters and impose a state of martial law ostensibly until order was restored. President Eisenhower, for example, planned to nationalize the various industries with hand-picked friends serving as plenipotent administrators for manufacturing, agriculture, and steel and petroleum production. The Postal Service would be tasked with registering the dead. The National Parks Service would run refugee camps. State-run banks would issue new currency. The Department of Agriculture would distribute rationed food. Secret legislation know as the Defense Resources Act was drafted that would lay out an entirely new structure and new roles for how the government would function during a national emergency, effectively suspending the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. It is worth noting here that many of these structures can be assumed to still be active. Author Garret M. Graff, who wrote a fascinating exploration of the U.S. government’s continuity plans in his well-researched book Raven Rock describes how many of the documents he requested are still classified as state secrets. Moreover, the scope of these plans is not limited strictly to nuclear war; they could be theoretically be activated in the event of any “national emergency.”

These contingencies would essentially entail the end of the American democratic project. Although continuity plans always included an assumption that normal functioning would be restored at some indefinite point following a catastrophe, like those mainframe servers which can’t ever be turned off because of the uncertainty that they would function the same way again if turned back on, it is unlikely that our current procedural democracy could be rebooted if it were suspended for any period of time. The workings are simply too complex, and too many of the people, places, and procedures that sustain it would have been destroyed, and once power was concentrated in juntas there would too much incentive to ever relinquish it.

Regional governments would therefore find themselves in a vacuum of uncertainty. National coordination would be difficult and expensive: with damaged road networks, it could take weeks to travel across the continental US. Communications would be limited to radio transmissions made from centralized stations. Air travel would be restricted only to flights of highest priority associated with national defense. States would turn inward to focus on their own difficulties and life for most people would assume a smaller, more local, and much harsher character. Where before the trend had been towards homogenization, regional differentiation would set in again, and after a period of years most people would have greater loyalties to the places where they had managed to settle and find life than any national ideals. Conversely, it would also be the age of great migrations. Millions would take to the fields and roads in search of refuge. They would overwhelm towns and states and nations. Some would be peaceful, and many would not. There is no predicting what the world would look like once these wandering people settled.

Warnings

I remember reading an article once which examined the murderous policies of “liberalism,” and asked “where is the pile of skulls marking the end of this ideology?” Fascism had the camps, Soviet communism had the gulags, but liberalism: nothing. Despite endless war, despite rampant crime, abortion, the bio-horror of transgenderism, the smothering security state, and the outright assaults on the middle class perpetrated by our own governments, the iron prison that entraps us has never been managed to be infamed with these outrages. Maybe it would literally require a nuclear war for us to turn our collective backs on it. With hindsight the logic of the system would become clear: because the system depends on stoking resentments from client peoples, it must continually destroy the social fabric of every place it touches to make new clients. At the same time, the powers of the system become directed for the purposes of its most radical elements: State Department Spokesperson John Kirby recently insisted that “'LGBTQ rights' are 'core part' of Biden foreign policy.” Therefore we go to war for fictions which can accept no dispute lest they collapse: because they have no internal validity or correspondence to reality even the smallest criticism can puncture them entirely, so now we risk nuclear death for transgender rights in Ukraine. Any pocket of resistance anywhere in the world must be rooted out with force or the whole edifice will crumble. With this logic at play, peace is an impossibility and escalation upon escalation, to the point of crisis and total finality, is inevitable. We ask ourselves: when it comes time to launch the bombs will the honor be given to a tr00n? Or will Victoria Nuland insist that she gets to do it herself?

So this is the warning for our elites: America is large and populous nation blessed with abundant natural resources and defensible borders. We would suffer horribly in the event of a nuclear war, but we would survive. The ideology of the ruling class would not. Its present control is maintained only through the most strenuous manipulations of every factor of life. If the cities were destroyed, along with its client classes and mechanisms of coordination, something new and distinctly American would step into the vacuum, but it would not have any resemblance to the old discredited system. Therefore let’s work for peace before you get us all killed.

A similar logic can be applied to other, somewhat less apocalyptic events. A financial collapse brought on by the hubris of central bankers, for example, would bring great suffering in the near term but remove their leverage for control. The resources required to maintain the current social order, based as it is on lies and contrary as it is in every way to human nature, are vast. You would think they would understand this. No doubt their predecessors appreciated it quite keenly. The current crop of elites by contrast, seem to think their positions ordained by God (maybe not the Christian God....) and therefore play chicken with catastrophe.

To the subject, I suspect the aftermath may be the Latin American century rather than the Chinese. First, because I doubt very much Asia would emerge unscathed. Second, because fallout world be a severe problem throughout the northern hemisphere in the event of a strategic exchange on such a scale. Nowhere is more irrelevant than Latin America, save perhaps Africa ... but we all Africa is dependent on food aid from a civilization that would be dead, so. Latin America, OTOH, can feed itself, provide its own energy, and is remarkably antifragile due to its political decentralization and, ironically, its corruption - things barely work there as it is, and the cities are quite accustomed to being barely functional islands of civilization in a sea of barbarism.

There's also Australia, of course, but even assuming they don't get drawn in, their population is very small. They may remain an outpost of relatively safe and prosperous civilization, but they would not dominate.

The predicted death count for the US is only for the first days. The vast majority of survivors would die of starvation within a few weeks.